“It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma…” — Winston Churchill

Passkey technology, along with WebAuthN based on the FIDO2 standard, is quickly becoming the go-to authentication method, replacing traditional email/password setups to enhance security and prevent data leaks. After the July 4th, 2024 ‘RockYou2024’ data leak exposed nearly 10 billion plain text passwords, along with several high-profile authentication breaches earlier this year, developers worldwide are urgently seeking a more secure solution. The Passkey standard, initially proposed by Microsoft, is emerging as the best-in-class technology to address these pressing threats. However, as a new standard, implementing it can be challenging for developers.

What makes Passkey superior to email/password methods and two-factor authentication is its foundation in public/private key encryption. This ensures that the interaction between a client device and the authenticating server is virtually unhackable by external parties. With no passwords involved, there’s nothing to guess or steal, even in the event of a server breach.

In the Passkey/WebAuthN protocol, the client device stores private keys on an encrypted keychain, accessible only through the user’s biometric data, such as thumbprints or facial recognition. The authenticating servers only store the corresponding public key, which, even if breached, is useless to a malicious party.

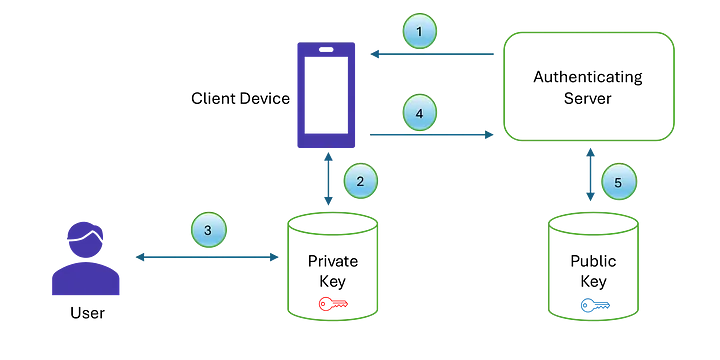

So how does Passkey work? Good question. The answer is actually quite simple, and it’s best explained with the following diagram.

First, a client device attempting to authenticate into a cloud account contacts the Authenticating Server and requests a randomly generated 128-bit challenge. Second, the client packages this challenge into an authentication data structure and signs it using the private key stored on its keychain, corresponding to the user’s key ID for the specific application. Third, the user is prompted for biometric authentication (thumbprint or facial recognition) to authorize the private key signing. Fourth, once the authentication data is signed, it’s sent to the authentication server for processing. Fifth, the server retrieves the public key associated with the key ID in the authentication data and verifies the signature. If the public key matches the signature, the device is authenticated; if not, the device is flagged as fraudulent.

Because the private key never leaves the client device’s keychain, it’s secure from malicious access. Without the private key, authentication is impossible. Unlike passwords, private keys can’t be guessed or leaked, and even the fastest computers today would take about 4 trillion years to crack them using brute force!

When a Passkey is first created for an application, it’s usually linked to a verifiable handle, such as an email or phone number. The legitimacy of this handle is confirmed by sending a six-digit code to the handle, which the user returns to the authentication server to prove ownership. Since the account doesn’t exist yet, there’s no risk of hacking. However, authentication servers must ensure that accounts aren’t created in someone’s name (or handle) without the owner’s explicit permission. This is where multi-factor code-based authentication plays a role during Passkey account setup.

The next question is: how does a developer handle a lost Passkey, and what does that actually mean? Since a Passkey is stored on a client device’s keychain, losing a Passkey typically means losing the device. This happens more often than you might think — mobile phones can be stolen or simply misplaced. If the user doesn’t have a backup device, like a tablet or desktop computer that shares the same keychain, access to their accounts could be suspended if the mobile phone is lost.

So, how can this be mitigated? If an iPhone or Android phone is lost, the keychain containing the Passkeys can usually be restored when the user purchases a replacement phone. In this case, access to accounts is only suspended until the new phone is set up and the keychain is restored.

Another strategy recommended by the Passkey consortium is to add a Passkey to a secondary device, even if it has a different keychain ID, as a backup. For example, an iPhone user could set up a second iPhone with a different ID for backup. Alternatively, the same user could use an Android device as a backup. This isn’t a concern if the iPhone user has an iPad or Mac that shares the same keychain and iCloud ID as their phone, since all devices on the same keychain will share the same Passkeys.

Lastly, there’s the scenario where a user might delete their Passkey from the keychain via the Settings menu, outside of the app itself. While this isn’t common, it can happen — chalk it up to user error. It’s important to remember that the Authentication Server only manages the public key part of a Passkey; the private key is controlled by the device’s keychain. Additionally, an application cannot programmatically delete Passkeys from a device’s keychain — this must be done explicitly by the user, as it should be. That said, some users might accidentally delete a Passkey and lock themselves out of an app, so there needs to be a way to handle this edge case.

The process to restore a Passkey would be similar to setting up the original Passkey. The user would need to follow the same steps they did during account creation. However, this should not be the default recovery method. If a user’s email or phone handle is compromised, a malicious actor could use it to set up a Passkey for more sensitive accounts. In fact, with email/password systems, account recovery is often the biggest security vulnerability. Distinguishing between a legitimate user in distress and a malicious party trying to gain access is challenging, if not impossible, to do purely through algorithms.

One solution might be to use a password for Passkey recovery, but that somewhat defeats the purpose of Passkeys. Another approach could require two multi-factor authentication methods — both an email and a phone — though even that could present vulnerabilities. The best strategy might be to rely less on algorithms and incorporate some level of human involvement. A few years ago, I had to recover a password for an email linked to critical server infrastructure at Google that had been managed by a former employee. This involved a good deal of paperwork — proving my identity and employment with the company — and a phone interview to resolve. If Passkey recovery is necessary for your application, it’s advisable to include some level of human oversight and maintain a solid paper trail.

For Passkey restoration, after contacting the application provider, the user with the lost key should receive a restoration confirmation code. This ensures that the application provider has approved the restoration, rather than it being an automated process by the Authentication Server. Once the confirmation code is issued — possibly with a time limit — the user can proceed with restoring their Passkey. During this process, ownership of the user handle (email or phone) would be re-verified through a second confirmation code.

For Passkey restoration, after contacting the application provider, the user with the lost key should receive a restoration confirmation code. This ensures that the application provider has approved the restoration, rather than it being an automated process by the Authentication Server. Once the confirmation code is issued — possibly with a time limit — the user can proceed with restoring their Passkey. During this process, ownership of the user handle (email or phone) would be re-verified through a second confirmation code.